How ancient cultures perceived peatlands and other wetlands (3000 BCE – 500 CE)

Most studies on the past development of mires, peatlands or wetlands in general derive from the discipline of palaeoecology, which is the “study and understanding of the relationships between past organisms and the environment in which they lived”, or more practically “the reconstruction of past ecosystems” (Birks & Birks 1980). Normally in modern-day science the past environment is reconstructed from a variety of biotic and abiotic proxies. One important source of information, however, is often overlooked: written accounts by eye-witnesses of past landscapes. There are vast gaps between the disciplines of biology, ecology and earth sciences and those of linguistics, literature, history and theology that need to be bridged in order to combine these totally different scientific branches.

This inspired us to have a more thorough look at ancient texts and to make an overview of the views on mires and wetlands by ancient cultures. We focus on Mesopotamia (Sumer, Babylon, Akkad, Assyria, Elam), Anatolia (Hittites, Hurrians, Luwians), ancient Canaan (Ugarit, Phoenicia and the developing Hebrew civilizations), ancient Egypt, and the ancient Greek and Roman civilisations. In total, the time-slice between c. 3000 BCE to 500 CE is covered.

Distribution of the ancient cultures discussed. A: Anatolia (Hittites, Hurrians, Luwians etc.).; Ä: ancient Egpyt; G: Greek city states and their colonies; K: Canaan (Israelites, Phoenicians, Ugaritics), M: Mesopotamia (Sumer, Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians, Chaldeans etc.); RK: Roman empire.

We distinguish a series of topics that can be recognised in all the various relevant cultures:

Topography

Topography includes predominantly the places were the specific mires and wetlands were located, which is mainly covered by the numerous geographical works known from Antiquity. But the topic includes places, regions or peoples named after mires too.

Descriptions of mires

Descriptions of mires and wetlands are rare, first of all because these landscape types were not always easily accessible, but secondly because most writings did not focus on wetlands but on subjects of which wetlands were only a part of the scenery. The subject ‘descriptions of wetlands’ does not only include the appearances of wetlands, but their flora and fauna too, of which especially the works on natural science by Theophrastus (‘Enquiry into plants’, ‘On the causes of plants’), Aristotle (‘History of animals’, ‘Parts of animals’, ‘On the generation of animals’), Dioscorides (‘On medical matters’), and Pliny the Elder (‘Natural history’) are important. Sculptures and pictures of animals and plants provide additional information on the ancient views on flora and fauna.

War

Wars were elaborately depicted by many ancient historical authors. Principally, mires and wetlands were used for three purposes in warfare: for hiding, for natural defences of cities, of camping armies, or in battle, and as a trap into which the enemy could be lured and killed.

Chaldaeans hiding in the reedlands for the Assyrian armies, c. 640-620 BCE, relief found in Nineveh and preserved in the British Museum; ©Trustees of the British Museum, shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/). Museum number 124774. Link to the photograph: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1851-0902-22-a.

Chaldaeans hiding in the reedlands for the Assyrian armies, c. 640-620 BCE, relief found in Nineveh and preserved in the British Museum; ©Trustees of the British Museum, shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/). Museum number 124774. Link to the photograph: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1851-0902-22-a.

Health

The relation between mires and health was twofold. First of all, there were medicinal qualities of various plants that were discussed elaborately by Theophrastus (‘Enquiry into plants’), Dioscorides (‘On medical matters’) and Pliny the Elder (‘Natural history’). On the other hand, it was thought that mires as landscape types had a very negative influence on human health – especially in the Roman culture, but this view already emerged among ancient Greek authors.

Human impact

Human impact included the use of vegetation, especially of reedbed plants, as raw material for building, packaging, weaving, fodder, writing material, weapons, musical instruments and many more. Reedlands were frequently hunted, primarily for food, but for pleasure too. Also pasturing of cattle often was in reedlands or other mire types. Hydrological regulation of mires dates back to the early beginnings of civilisations. In the ancient Egyptian society agriculture was in the floodplains of the River Nile after the river had deposited fertile silt during the annual inundations. The agriculture connected to this flooding required an ingenious irrigation system and a thorough understanding of hydrological processes, as well as a central authority that planned and structured the hydrological projects. The summit of hydrological regulation is complete drainage or filling-up of peatlands. The city of Rome was built – in-between and outside the famous seven hills – in floodplains of the River Tiber. Major valleys subject to flooding were the Velabrum maius (where the circus Maximus was located) and the Velabrum minus (with the Forum Romanum), and initially the city was plagued by floods and water surplus. According to Livy (‘History of Rome’ I:38), Lucius Tarquinius Priscus – the mythological 5th king of Rome – organised the construction of the cloaca maxima around 600 BCE to drain the forum and the Velabrum minus. Soon other cloacae were constructed to drain other parts of the city. Although originally open canals, in later days buildings were erected haphazardly covering the cloacae (Livy, ‘History of Rome’ V: 55), with as result that nobody knew their precise locations anymore. The cloacae were primarily constructed for water discharge and were not used for sanitation purposes prior to the early imperial period.

The question arises whether peat was extracted from mires as resource. From the texts seen by us it appears that peat as substance was not known or used in antiquity, or at least nobody wrote about it. There is one exception: Pliny the Elder (‘Natural history’ 16:1.4) mentioned how the Chauci – a Germanic tribe in present-day northwestern Germany – used some kind of mud for cooking and heating. It is clear from his description that this mud was burnable, and it is almost unambiguous that this was peat.

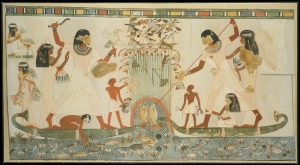

Facsimile of an Ancient Egyptian fishing and fowling scene in papyrus reeds, from the tomb of Menna, Thebes (c. 1400-1350 BCE). Various fishes, birds and other animals are displayed, as well as papyrus and water lilly. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Facsimile of an Ancient Egyptian fishing and fowling scene in papyrus reeds, from the tomb of Menna, Thebes (c. 1400-1350 BCE). Various fishes, birds and other animals are displayed, as well as papyrus and water lilly. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Religion

Religious aspects of mires and wetlands: The polytheist religions of ancient times were manifold, and numerous gods were connected to wetlands. However, wetlands played also a role in various creation myths, in great flood stories, and in the perception of the afterlife. In the Egyptian religion, the final destination of the deceased was the sekhet iaru, which is difficult to translate. Sekhet can mean field or marshland, iaru translates as reeds or rushes. This area was probably imagined as a gigantic Nile Delta-like landscape including interconnected river branches and marshes, but agricultural fields as well. Furthermore, there was the sekhet hetep or hotep that had ample water courses and various cities and islands. Hetep translates as offering, rest, or peace, but also signifies the state of being at peace, being at rest, or being satisfied. The road to the afterlife realms was long and dangerous, and the well-known ‘Pyramid texts’, ‘Coffin texts’ and ‘Book of the Dead’ presented ample instructions and spells how to get their unharmed, and also give detailed information how both sekhets were envisaged.

Sexuality

Sexuality: A connection between wetlands and sexuality probably initially appears strange, but there were various wetland-related stories that had a highly erotic content. Especially Sumerian texts were often explicitly sexual, but also the Egyptians envisaged reedlands as excellent places for the sexual act.

First insights

In ancient Mesopotamia the extensive wetlands of the Rivers Euphrates and Tigris were seen as something beautiful, which relates to the fact that Mesopotamia societies were completely dependent on the wetlands for raw material, food and daily life in general. However, some negative connections were perceived also. In ancient Egypt, similarly, the societal focus was completely on the River Nile and its floodplains. However, in the secular literature seen by us the wetlands were mainly merely a part of the scenery and not something special. In the Egyptian religion, on the other hand, wetlands were very dominant, culminating in the marshes of the afterlife. Ancient Canaan was a warm and dry regions were only few mires have developed, and consequently wetlands do not play an important role in Canaanite texts. Whereas ancient Anatolian and Greek literature seems to have had a rather neutral to slightly negative attitude towards wetlands, the Roman ruling and cultural elite completely detested such landscape types: this will predominantly be the result of the difficulties in the city with the mires in the floodplain of the River Tiber. It is, however, evident that the more rural people were less negative and reclaimed wetlands according to their needs. All societies developed the necessity for wetland management which resulted in ingenuous hydrological technology. It is safe to assume that the mires and wetlands played an important – if not crucial – role on the way the different civilisations developed technically, agriculturally, and socially.

Outlook

We plan to present our research in a series of papers covering various aspects of the role of mires and wetlands in ancient cultures. Simultaneously a series of short columns was initiated in the Bulletin of the International Mire Conservation Group that regularly presents single quotes from ancient works. It would be interesting and valuable to extend this kind of research to other areas in the world where ancient literature or visual art may give information on the role of mires and wetlands, and we hope to encourage experts from all over the world to join our objective: it will result in an overview at the crossroads between nature and culture, and will enrich both the (palaeo)ecological sciences, and those of history, archaeology and linguistics.

This research is carried out in close cooperation with Hans Joosten, Immanuel Musäus and Jasmin Hettinger.

Publications:

De Klerk, P. (2017): 2500 years of palaeoecology: a note on the work of Xenophanes of Colophon (circa 570-475 BCE). Journal of Geography, Environment and Earth Science International 9(4): 1-6; article no. JGEESI.32198.

De Klerk, P. (2019): Peatland poetry from the past: The Calydonian boar in the Metamorphoses by Ovid (43 BCE – 17/18 CE). IMCG Bulletin 2019-06 (November-December 2019): 13-14.

De Klerk, P. (2019): Peatland prose from the past: the trembling soils of Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE). IMCG Bulletin February-March 2019: 3.

De Klerk, P. (2019): Peatland prose from the past: the indulgent and exorbitant mires of St. Ambrose (340-397 CE). IMCG Bulletin April 2019: 2-3.

De Klerk, P. (2019): Peatland prose from the past: the Sudd in the south. IMCG Bulletin 2019-05 (August-October 2019): 7-12.

De Klerk, P. (2021): Peatland poetry from the past: the headgear of river gods in the works of Virgil and Ovid. IMCG Bulletin 2021-2: March – Apr. 2021: 5-7.

De Klerk, P. (2021): Peatland prose from the past: The displeasing land of Cabul (NW Israel). IMCG Bulletin 2021-6: Nov – Dec 2021: 18-21

De Klerk, P. (2022): Peatland prose from the past: Ancient Egyptian camouflaged mires in the works of Diodorus of Sicily (1st century BCE) and Frontinus (c. 40-103 CE). IMCG Bulletin 2022-1: Jan. – Febr. 2022: 4-6.

De Klerk, P. (2022): May your reeds be great reeds – a collection of essays on reedland texts and pictures from ancient cultures. Proceedings of the Greifswald Mire Centre 02/2022, 43 p.

De Klerk, P. (2024): Peatland paintings from the past: A picture of a wetland described by Philostratus the Elder (ca. 190–230 CE). Mires and Peat 31: Article 11. doi: 10.19189/MaP.2024.OMB.Sc.2417895

De Klerk, P. (2024): Peatland proverbs from the past: buying the marsh with the salt (Aristotle, 384–322 BCE). Mires and Peat 31: Article 20. doi: 10.19189/MaP.2024.OMB.Sc.2473372

De Klerk, P. (2025): Peatland poetry from the past: the neighbour of Catullus (first half of the 1st century BCE). Mires and Peat 32: Article 16. doi: 10.19189/001c.144175.

De Klerk, P. & Joosten, H. (2019): How ancient cultures perceived mires and wetlands (3000 BCE – 500 CE): an introduction. IMCG Bulletin 2019-04 (May-July 2019): 4-15.

De Klerk, P. & Joosten, H. (2021): The fluvial landscape of lower Mesopotamia: an overview of geomorphology and human impact. IMCG Bulletin 2021-3: May – June 2021: 6-20.

De Klerk, P. & Joosten, H. (2024): The hippopotamus and the maned river horse: descriptions of an Egyptian wetland mammal in ancient Hellenic and Roman texts. Journal of the Hellenic Institute of Egyptology 7: 119-132. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.15301552

De Klerk, P., Musäus, I. & Joosten, H. (2020): Famicose peatlands and ungulate hoof diseases: on the meaning of a word from ‘On the meaning of words’ (Festus, 2nd century CE; Paulus Diaconus, 8th century CE). Mires and Peat 26: Article 22. doi: 10.19189/MaP.2020.OMB.StA.2018

De Klerk, P., Musäus, I. & Joosten, H. (2022): Feuchtgebiete in Mythos und Religion alter Kulturen: eine Einführung. TELMA 52: 91-108.

De Klerk, P., Hettinger, J., Musäus, I. & Joosten, H. (2022): Zitternde Böden und brennender Schlamm: die Wahrnehmung von Moor und Torf bei den Römern. TELMA 52: 109-128.

De Klerk, P., Hettinger, J., Mulder, C., Musäus, I. & Joosten, H. (2025): De paludibus urbis Romae: Ancient Romans on the wetlands of ancient Rome – a palaeoenvironmental perspective. Orbis Terrarum 23: 39-93. doi: 10.25162/9783515140423

Mire quotes from Antiquity

“Enki shouted: “by the life of An I demand: lie down in the reeds, lie down in the reeds: it will be a pleasure!” (from the Mesopotamian legend of ‘Enki & Ninhursag‘)

“So, I went down into the marsh close to the pastures, and there I saw a woman who did not look human at all. My hair rose when I saw her bristled hair, and her hairy skin. I will never do what she said, and fear still runs through my limbs.” (from the ancient Egyptian ‘Tale of the herdsman‘)

“The general’s night was disturbed by a disturbing dream: he saw Quintilius Varus rising – covered in blood – from the mire, and heard him calling. But he refused to obey and pushed him back when he hold-out his hand.” (Tacitus ‘Annals’ – Book I)

“The Egyptians, before a battle on a plain near a marsh, covered the mire with seaweed, and then, when the battle began, they feigned flight and drew the enemy into a trap: then these, while advancing too rapid on the unfamiliar ground, were caught in the mire and surrounded”. (Frontinus ‘Stratagems’ – Book II)

“I have a neighbour whom I wish to fall head over heels from your bridge into the mud; — but let it be at the blackest and deepest pit of the mire with its stinking morass.” (Catullus ‘poem XVII‘)

“If you have to cross a mire, let your horse be the first to test its depth.” (Claudian ‘Panegyric on the fourth consulship of emperor Honorius’)

“When he [=emperor Probus] had come to Sirmium in the hope to enrich and enlarge his birth city, he ordered several thousand soldiers to drain a nearby peatland and to construct a large canal with outlets flowing into the Save in order to provide the people of Sirmium with new lands. However, the soldiers rebelled and pursued him into an iron-clad tower, which he himself had built very high as a look-out. The soldiers slew him there in the fifth year of his reign.” (Group of authors, ‘Historia Augusta’)

“Varus, who was betrayed by a freedman, ran away. After wandering from mountain to mountain he reached a marsh at Minturnæ where he rested. The inhabitants of Minturnæ, however, guarded this mire in search of robbers, and the motion of reeds revealed the hiding-place of Varus.” (Appian ‘Civil Wars’ – Book IV)

“…and the atmosphere around it was highly pure and good for the health of humans. Then there was neither a marsh nearby as a source of oppressive and filthy vapours, nor were any vapours brought in from outside.” (Dionysius of Halicarnassus ‘Roman Antiquities‘ – Book XII)

“If you have to build on a river bank, do not build the front facing the river, since it will be extremely cold in winter, and unpleasant in summer. Such precautions need also be taken in the neighbourhood of mires for the same reasons, but also because there are certain miniscule creatures that are invisible to the eye but hover in the air and enter the human body over the mouth and nose and cause serious diseases.” (Varro ‘On Agriculture‘ – Book I)

“Hannibal, whose eyes were suffering from the annoying spring weather that alternated between hot and cold, rode his sole surviving elephant in order to be higher above the water. But sleep deprivation, moist nights, and the air of the marshes affected his head. Since he had no place and no time to allow for healing, he lost the sight of one of his eyes.” (Livy ‘History of Rome‘ – Book XXII)

Your e-mail address will not be published.